Coming soon

This is Dog on the Road, a brand new site by Ryan Singel that's just getting started. Things

LOOKOUT dives into why Arizona’s gay bars aren’t taking overdoses seriously, and who’s doing something about it.

According to her family, Valerie Lucas had trouble dealing with high-stress situations.

Her mother, Heather Lucas, said her daughter was an extrovert by all definitions: She was the first to dance at a party; If there was a debate between going out with friends or staying in and watching a movie, the former was the correct choice.

“She was not a homebody whatsoever,” Heather Lucas told me. “She was very, very smart. And I think that was part of the issue, was the emotional side. She just didn't know how to deal with everything.”

It’s a story many young women have faced. Logic was easy enough to work with. But emotions—those were more difficult to process. And just like other young people battling through tough times, it was easier to dive into binge drinking, which led to irresponsible drug use, which led to even worse decisions.

In Valerie Lucas’s case, she was 13 when her father died, which is also when she began using heroin.

Like many mothers who tried to manage a teenager falling into serious drug use, Heather Lucas didn’t know how to cope. But she knew what prison could do to her little girl, and she didn’t want to risk reporting her to authorities.

At some point, though, drugs took over. A robbery while Valerie Lucas was high led to a three-year stint inside Perryville Correctional facility, Arizona’s all-woman prison.

While inside, Valerie Lucas started dating another prisoner. Both women were forced to work at Hickman’s Egg Farm in Tonopah, Arizona during their incarceration. After Valerie Lucas’s release, she and her girlfriend continued working at Hickman’s, and the two became inseparable, her mother said. In May 2021, Valerie’s girlfriend died of an overdose, a mixture of fentanyl and alcohol at her apartment off-site from the farm, according to a Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s report.

Soon after that, her grandfather passed away—another emotional blow that Heather Lucas said her daughter took to heart. “I just think she didn’t know how to handle it,” Heather Lucas said. “The stress. It just — she just couldn’t deal.”

Probation notes for Valerie Lucas, gathered by LOOKOUT through a records request, mentioned a friend—whose name was redacted—dying of an overdose, and said that Valerie swore off drugs. “You just don’t know what's in it,” she told the probation officer, according to the report.

But just a few days later, the probation officer logged an additional note to Lucas’s file. They needed a death certificate to close her case. Valerie Lucas had died of an overdose.

I met Heather Lucas while working on a story about drug-related deaths of people who leave prison. As I spoke with her and others who knew Valerie Lucas, it made me wonder what could be done within the LGBTQ+ community when it comes to overdoses and drug usage.

In 2022, more than 1,900 people died of overdoses in Maricopa County. Nearly half of those deaths happened in Phoenix. Beyond geography, there is little data to account for overdoses within the LGBTQ+ community, both nationally or statewide.

But public health researchers say they know it's there: The first hint of a national LGBTQ+ drug problem emerged in 2015. The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration did a health study that showed sexual minorities had abused opioids far more than their straight peers across multiple age groups. In 2019, six heads of research across Canada published a letter in the medical journal The Lancet, pleading with the U.S. and Canadian governments to start tracking and monitoring drug use and overdoses across both countries in regards to LGBTQ+ people. Since that plea, little has been done on a federal level.

That’s not incredibly uncommon. Often, federal agencies don’t have the best tools to get granular data, which leaves local governments to figure out who is being affected by specific public health crises.

The sense of urgency to address LGBTQ+ opioid abuse has not yet filtered down to Arizona. In 2018, the state did recognize it as a problem in a needs assessment report done by a third-party administrator. But on the state health department’s website, as well as the Maricopa County Health Department’s data portal, there still is no way to track how the overdose epidemic is affecting our community. As a result, it’s unclear how bad our drug epidemic might be.

Arizona isn’t alone in this dearth of local data. Many other cities with large queer populations—Seattle, Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco, to name a few—have turned to queer spaces, like gay bars, to carry Narcan. Also known by its generic name naloxone, Narcan is an overdose-reversing drug and has become a staple in first-aid kits. The nasal spray works within minutes and the intravenous needle has even better uptake in reversing an overdose.

But in Arizona, many LGBTQ+ bars across the state (primarily in Phoenix and Tucson) have yet to even acknowledge a problem.

I contacted 20 of Arizona’s gay and lesbian bars and surveyed them on their use or knowledge of Narcan. Only 12 responded. Of those who did, most staff were unfamiliar with Narcan. Others who were familiar with Narcan dismissed the need for such a life-saving drug in their businesses, pushing back saying their establishments were “drug free,” or that they didn’t want to “face liability” for having the drug on hand. Only a few said they had trained their staff on how to use Narcan and it was something they had on hand.

While many queer spaces are failing to help keep their community safe, there is a small group of people across various organizations in Arizona working to change the way people view drug use and to see that the owners of queer spaces start doing their own part.

For those who only deign to visit Phoenix’s most populous corridor in midtown—the area surrounding Steele Park and over to the Veteran Administration Hospital—it’s often referred to as a dump or a “ghetto.”

It’s true to a mild degree; the area has its stragglers and vagabonds. But it’s an important location for queer history in Phoenix, if only because it’s where the yearly Pride festival is held.

There’s another gem around the area, blocked behind brown-tinged gates and brick walls, working to help fight the opioid crisis within queer spaces–and he’s just under 6-feet tall.

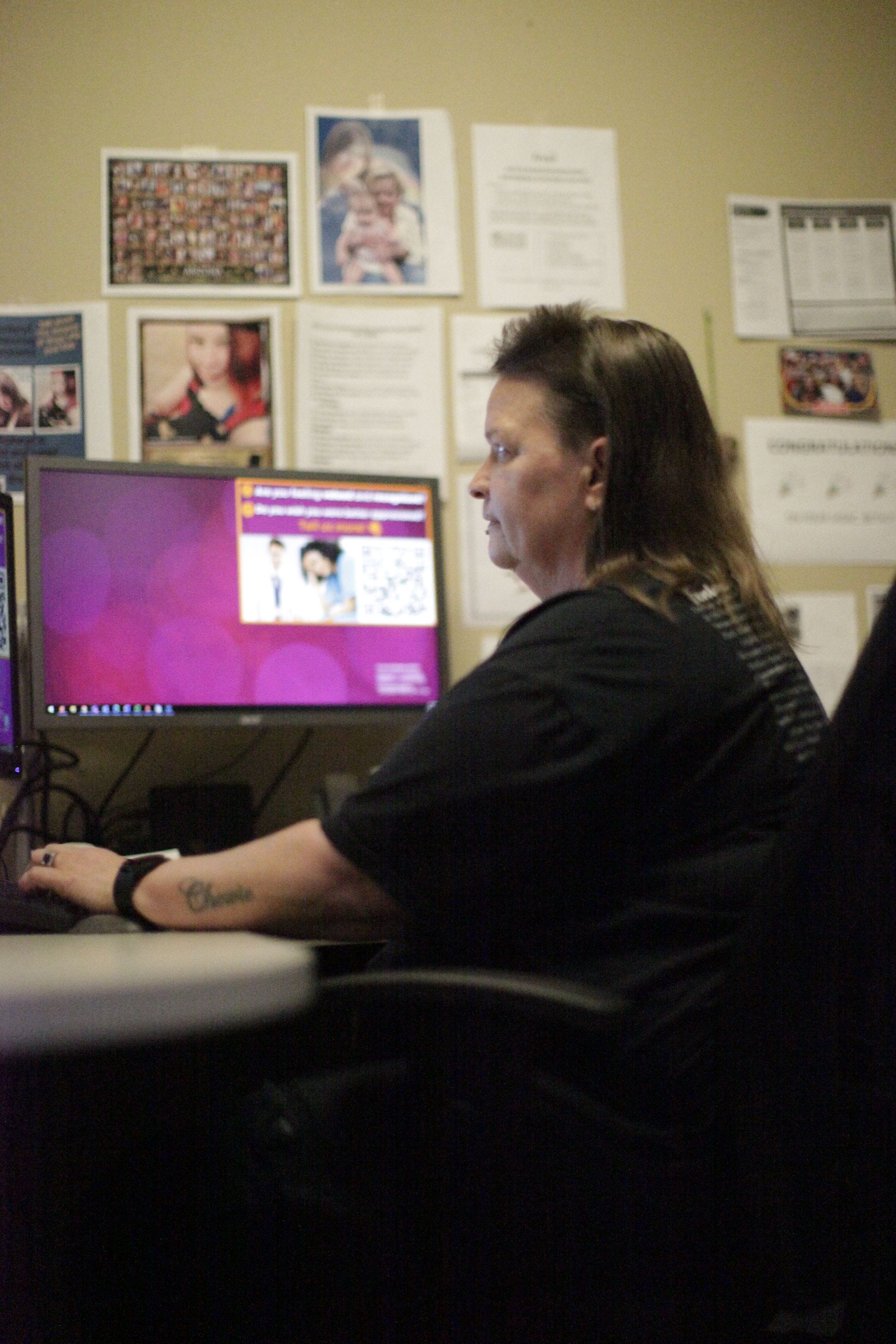

When I first walked into the medical center where Al Chapoy worked as a social worker, I was taken aback. I have spent many hours, both in my personal and professional life, inside medical centers. For the most part, they all have the same feeling: clean, cold, and sterile.

Photos by Moses Martínez

Chapoy’s office, though, had a bit more whimsy than I was used to. And it all made sense when I sat down at his desk.

It was a mess, cluttered with pamphlets and worksheets. A gallon-sized Ziploc bag overflowed with drug test strips and empty nasal spray bottles which he said he uses to demonstrate how to save a life using Narcan or test drugs for fentanyl.

Chapoy reached into the Ziploc bag and pulled out a small white nasal spray. It was Narcan. The device, itself, looks a bit like an all-white toy rocket, the kind you’d win in an arcade machine. The drug inside, naloxone, acts as an inhibitor for opioids.

The drug was introduced in the 1970s and given to paramedics to reverse overdoses. For a while, you’d only see Narcan inside ambulances. But that changed when the opioid epidemic made its way into the white-rural enclaves of Appalachia.

As a result, more first responders began carrying the drug. It wasn’t just paramedics. Firefighters and cops were carrying it, too.

The spread of fentanyl in recreational drugs over the past five years has meant that overdoses can literally happen anywhere, at any time, and with any amount of drug.

For example, Chapoy explained, a bag of cocaine often has what he calls a “chocolate chip effect,” which means that a bit of fentanyl can live in one part of the bag, and not infect the rest of it.

When you take any kind of opioid—from a painkiller prescribed by your doctor to that tiny bit of fentanyl that has become more likely to turn up in bags of your favorite party drug—the opioid latches onto receptors in your brain that slow your breathing and moderate pain. Take too much, and the receptors stay stuck, then you stop breathing. Once introduced into the body, naloxone immediately takes the opioids off the receptors within moments.

The easiest way to get the drug into someone is through the nasal spray, which is what Chapoy held in his hand. Once you put the shaft of the rocket inside the nose, you press the middle plunger and the drug is inhaled, even if the person overdosing doesn’t seem to be breathing.

When Chapoy got his job, he went out on a limb and took a box of Narcan to gay bars, places like Stacy’s, Pat O’s Bunkhouse, or Kobalt, where he knew it would be welcomed. He wasn’t supposed to do it, legally. But, he said, there was a hidden need within queer spaces and groups.

At one point, there was an entire roster of spaces that wanted to get trained in Narcan usage, which included how to use the nasal spray, along with the injectable form that goes into someone’s leg. Chapoy also trained staff at these spaces on how to spot an overdose: pale skin, sweaty, short of breath, wide pupils.

“Whenever we start to have the conversations where they actually allow us to go ahead, they're receptive to the idea of having these trainings in their businesses, they actually get pretty excited,” Chapoy said.

But with the COVID-19 pandemic, funding disappeared and overdoses became more prevalent, and at the same time, many queer spaces pulled back on carrying Narcan.

He pointed to the calendar behind him: “Before COVID, this whole thing was filled,” he said, mentioning that he had talks with people at many different queer spaces (he calls them Rainbow places). Now, there are only a few dates filled out for the whole month of August.

For months, Chapoy has tried to go back into gay bars and make a point that they need to have Narcan available. But he’s received nothing but pushback from owners and managers who falsely claim they would be held liable if anything went wrong with administering the drug. Other spaces are claiming that they are “drug-free” and don’t want to condone illicit drug usage in their space.

“The reality is that there are people doing drugs in these spaces,” he said. “Whether you say you don’t want it to happen, or not.”

The Anvil bar on Thomas Road and 24th Street is as close to a classic leather bar that Phoenix has.

I’ve been to The Anvil many times. I danced there every now and then, sat on the back bench of the patio corner a handful of times more, and I’ve seen dozens of people do bumps of cocaine in multiple corners. In broad daylight, I was once asked if I was selling drugs.

But when I called The Anvil to ask if they had Narcan, the response I got shocked me.

“What? Do we have what?” the employee asked.

“Do you have naloxone, or you might know it as Narcan? It helps reverse overdoses in the event there’s one on your property,” I responded.

The bartender on the phone was miffed in my questioning. “This is a bar,” he said. “We don’t have drugs.”

I then asked if they’d be open to anyone coming in and talking to them about having Narcan on site, and I was politely told no.

But it wasn’t just The Anvil’s response that made my head go sideways. BS West, the only gay bar in Scottsdale, doesn’t have Narcan and the staff has never done training. My reporting revealed that Oz Bar, The Rock, and Bar1 also are Narcan-free zones.

When I called IBT’s in Tucson, the bar manager who answered the phone explained they didn’t have Narcan because, “We are a successful bar and we don't want to be associated.”

Of the businesses I called, only four—Stacy’s, Charlie’s, Kobalt, and Flex Spas—have naloxone available.

The westside of Phoenix, for those who have never been, looks vastly different from the East.

There’s more congestion and greenery as you head East, closer to downtown and beyond there into the East Valley. But on the westside around 27th Avenue and Indian School, it’s more industrial, with miles of single-family ranch homes and strip malls. It’s more suburban, and it’s where the best tacos usually exist.

It’s also where Beth Joly works.

Joly and I first meet in the waiting room of her office at Terros Health. From the entrance to the back wall, there are signs promoting Narcan, and how to properly clock the signs of an overdose. On the back glass divider, which separated the waiting room from the offices, hangs a picture mural of everyone who has died of an overdose across multiple states.

Joly walks out in an oversized black tee shirt, a giant black metal chain hung across her neck, a tight mullet sprouted from her head, and has a labret piercing, all tinged with the smell of cigarette smoke. Her voice is powerful, but incredibly friendly.

Beth Joly at her work at Terros Health holding up a photo of her sister who died of an overdose (left). Photos by Joseph Darius Jaafari

I had heard of Joly through the grapevine multiple times, that she was doing impactful work in creating access to Narcan and getting people into recovery. She was a one-woman advocacy group, making a difference in people’s lives and showing up for legislative testimonials.

Joly starts off by telling me that she’s been in recovery for almost a decade. She did time in Perryville prison, and a few years ago got her wife into recovery. Her sister, who overdosed from fentanyl, is why she got into harm reduction.

Her office is exceptionally clean yet littered with pictures of people who have died and molded her worldview of how serious the fentanyl problem has gotten: “The reality is that this shit is everywhere,” she said. “And if you don’t think it’ll ever happen to you, you’re wrong.”

When I told Joly about what we found in our reporting about gay bars in Arizona not providing Narcan training to their staff, she guffawed.

“Why don't you just take a look at the Good Samaritan Law,” she said. She’s referring to the law passed last year that allows all private citizens, including business owners, to step in and help someone in the case of an overdose without legal repercussions if the situation turns fatal. “So why not protect yourself with something that could save a life? Would you rather have someone dead in your bar? That seems like more of a liability.”

It’s a common problem, said Alexis Moran, a care navigator at Shot in the Dark, which is a rag-tag group going into parking lots at night and handing out harm reduction supplies, such as naloxone, clean syringes, and other products.

Moran, who uses they and them pronouns, said there is a lot of misinformation around the use of Narcan, but more often it’s a problem of empathy. They explained how only a few weeks before we spoke, someone overdosed in a Safeway parking lot in Scottsdale.

“I went to grab my Narcan out of the car, and the people, you know, surrounding me just, you know, were shouting their comments like, ‘What if he's allergic,’ ‘Why do you have that?’,” they said, adding that they eventually brought him back from the overdose.

And out of that entire experience, Moran said they left livid with the other people who stood by.

“I was angry at the questions, or people telling me that I'm an angel, and saying that I saved my spot in heaven. That kind of made me mad,” they said. “So it wasn't so much about like, yeah, I saved this man's life. It was, ‘Why the fuck couldn't you guys have?’”

When I told Moran about the response of the employees and managers at the gay bars I spoke with, they sighed heavily: “People want to complain about how many people are using drugs, but just turn a blind eye to it and not be part of the solution,” Moran said. “You could literally have someone dying in front of you and the ability to save them, and they still say no.”

Moran’s comment rang through me, and left me with a sense of hopelessness. Who can we trust, if not the people with power in our community? Do the people who own and manage our dedicated safe spaces care if we live or die?

But it also left me with a bit of hope, that maybe they’ll get to see the power of someone being revived back to life in front of them, and possibly asking themselves the question Moran asked of others: “Why aren’t I doing this?”